Photos courtesy of the University Archives

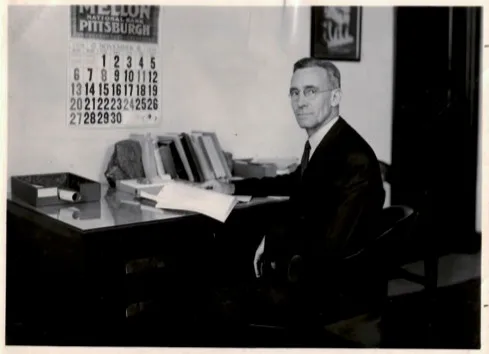

When AUC was still a dream, Wendell Cleland, assistant to AUC's founding president, Charles Watson, played a pivotal role in the early vision of the University. Setting out to Cairo to study Arabic and see how viable establishing a university would be, he left the United States in 1917, during World War I. Cleland crossed the Pacific, traveling up the West Coast to Canada, then to Japan, China and India, before passing through the Suez Canal to Port Said.

"But the day we arrived at Port Said, the United States declared war on Germany. ... We had a communication from the Board of Trustees over here and Dr. Watson that they had decided that if a war was going on there that involved Egypt and the threat of the Germans, that there wasn't much opportunity to promote the growth of a new university in Egypt."

After the war, AUC began operations in 1919. Cleland notes that there were many graduates of secondary schools or the Egyptian University who were interested in taking classes at AUC.

"I was appointed to organize, according to the demand of the local community, classes for those who wanted to study certain subjects. And that eventually resulted in the 'Qism Khidma 'Aama,' the extension division of the University, where adults could come along and take courses and eventually get degrees and build up their own esprit de corps and improve their jobs." AUC's School of Continuing Education (SCE) was established in 1924 as the Division of Extension, with Cleland serving as director until 1947.

Local Connections

In the beginning, the school's primary aim was to engage and serve the Egyptian public through lectures, film screenings and outreach programs.

For Cleland, connecting the local community with AUC's foreigners and boosting the school's reputation was of major importance. He describes how the public lectures that began with the Division of Extension were a crucial factor in achieving this goal.

"... We did a good deal of publicity and got speakers speaking in Arabic, including Taha Hussein ... and Al Azhar students would come down in great bulks to take these lectures. ... That built a kind of spirit of goodwill between the foreigners, the Americans, and the local people."

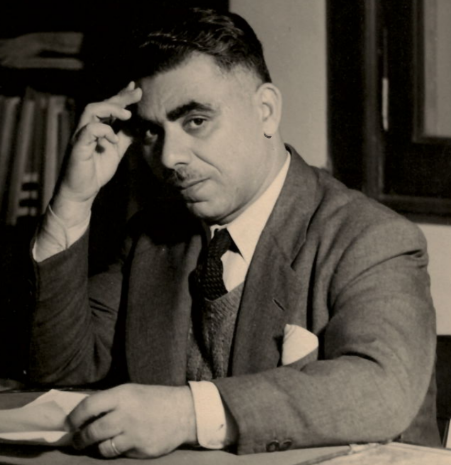

Hanna Rizk, who served as Wendell Cleland's assistant director starting in 1925 and later took over as head of the division before going on to become the first Egyptian vice president of AUC, reflects on the unique freedom afforded to the program's lecturers in one of his reports:

"It is worthy of note that we never place any restrictions on what our lecturers may say and occasionally they may have been surprised when I have told them so. It is also remarkable that the freedom of our platform has never yet been abused by any lecturer."

Rizk's emphasis on the freedom of expression within the division was also reflected in his encouragement of more small-scale and ongoing conversations at AUC about current events. The American University in Cairo: 1919-1987 by Lawrence R. Murphy (AUC Press, 1987) highlights the fact that, "In addition to large lectures, Rizk arranged smaller forums where questions of critical importance to Egypt could be discussed by a more select audience."

The school also screened films at Ewart Memorial Hall and beyond. Ghali Amin, an AUC graduate who worked for the division, noted in his oral history interview that the school began having weekly cinema shows after his first year in order to raise money. This began in 1934 "when families didn't go to public cinema, nor girls alone."

A season ticket cost 25 piasters for one seat in the hall and 30 for the balcony. The films were typically historical, social, scientific or based on literature. King of Kings, a 1927 film that depicts the last weeks of Jesus's life before crucifixion, was shown to a Christian-only audience 20 to 30 times per year around Easter.

"Once Cecil B. Dellille [the film's director] was in Cairo before Easter time. They took him around Ewart Hall to show him the poor Christian families who had come to see the film." Rizk added in a 1947 report: "The King of Kings film is not exhibited in Egypt in any place other than in Ewart Memorial Hall."

It was during this time that Umm Kulthum, the Palestine Orchestra and other major artists performed at Ewart Hall. "AUC was selected because of its good acoustics for recording," Amin said. Despite tumultuous times in Cairo and beyond, attendance remained consistent. Even during World War II, when there were air raids during shows and people would leave the theater into a blackout, "Programs [were] as popular as usual; films came as usual."

Health and Welfare

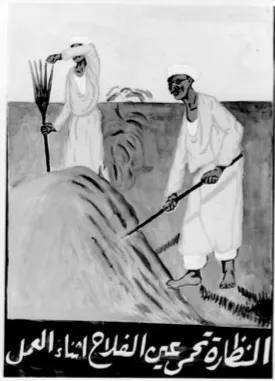

In the early days of the University, Egypt's rapid population growth prompted the Division of Extension to send its students to visit villages outside of Cairo. Their goal was to assess the challenges faced by the residents and explore ways to help. Cleland recalls the efforts in his oral history interview:

"... It was rather amazing the degree to which the local villagers accepted this kind of aid. We didn't ask them for anything; we offered just to help them."

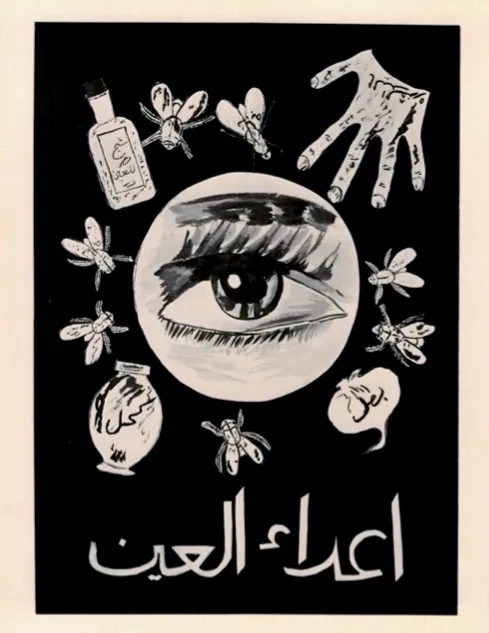

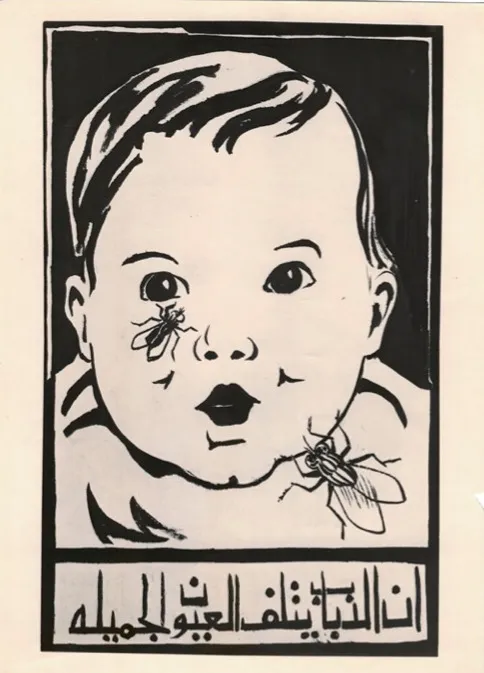

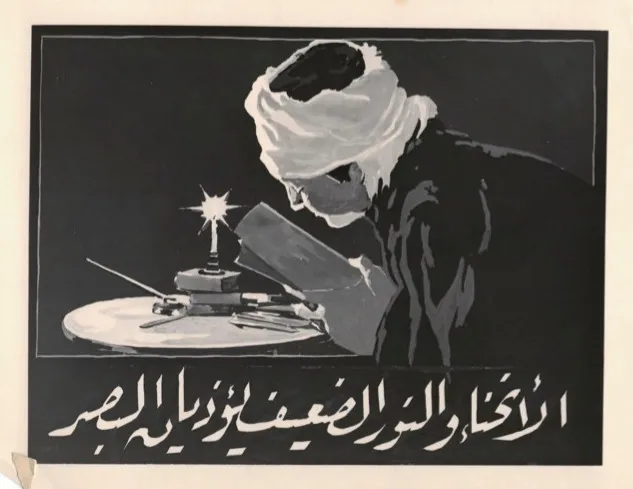

One of the school's most successful public health campaigns, launched during this period, was the "Save the Eyes" initiative -- whose name was chosen by Rizk and approved linguistically by Taha Hussein. The campaign aimed to raise awareness of eye hygiene and prevent blindness, a pressing concern in Egypt's rural regions. By distributing leaflets, screening educational films and hosting local events, the campaign helped to address a critical health issue while demonstrating the division's ability to engage directly with the public.

The school also opened a Child Welfare Clinic in Cairo's Sayeda Zeinab neighborhood in late 1925. During its first six months of operation, the center served 1,294 people, giving 5,056 treatments, mostly to women and children, and operating a small girls-only school, according to minutes from a 1926 Board of Trustees meeting.

The report describes the clinic's location and services:

"The American tourist who occasionally visits this center first gets a ride through narrow, thickly populated streets, where an automobile has to creep and a few drops of rain make mud for two weeks. Just behind the famous tomb-mosque of Lady Zeinab, granddaughter of the Prophet, and near three other mosques, he descends from his car ... Up narrow stone steps he goes to the second story and there he is ushered into a bright, clean reception room from which he can watch events."

A visit to the clinic cost two and a half piasters; however, no one was turned away for inability to pay. Patients could also enjoy demonstrations on childcare, nutritional counseling, advice on cheap materials for creating cradles and bathtubs at home, and religious lessons.

Evolving with Egypt

Throughout the years, SCE's curriculum has always been set based on the needs of the public. According to Osman Farrag, director of the Division of Public Service from 1966 to 1973 and professor emeritus of psychology, the school offered free courses in psychology, family planning and care for children with disabilities.

He describes in an oral history interview how many of the division's courses came to be during his tenure, and specifically how one conversation he would never forget launched one of SCE's most successful programs.

"A student [who] was studying English came to me and said, 'I am a chemical engineer and I am working in a textile factory. ... Suddenly after ten years I have been promoted and became the president of the company. I have 150,000 workers ... I am lost. ... I haven't had any experience in management or administration."

The student told Farrag that there were many like him -- teachers who became headmasters and doctors who were promoted to heads of hospitals. All of them had the same problem: they didn't know how to lead. "We started to offer this [business and public relations] program which flourished and is one of the most important areas of study at AUC now," Farrag said.

Similar stories led to the development of other tailored courses. Farrag describes special programs that upskilled government employees in

Egypt's ministries, such as a massive training program for agricultural workers under President Gamal Abdel Nasser's land reclamation program, and specialized English courses for diplomats, doctors, lawyers, businessmen and legislators. Under Farrag, the school also offered decoration engineering for movie producers and theaters, playwriting and secretarial studies, which was one of the most sought-after courses, he recalls.

"I had at that time a big problem facing the huge number of applicants who [wanted] to attend this course. To the extent that the police sometimes interfered in order to solve our problem because the pressure was tremendous. Why? Because in banks a good secretary can get starting from 3,000 pounds a month to 15,000 pounds a month. The AUC graduates in other departments cannot get this [much], so we used to receive applications from AUC graduates themselves. ... We used to accept about 200 every semester."

A Spirit of Service

To understand the SCE's commitment to community and service, one need only look at its administrators. Mohamed El Rashidi, who worked in the Division of Public Service and its successor, the Center for Adult and Continuing Education, from the late 1960s to the early 2000s, embodied this ethos, as his dedication often extended beyond his official role at AUC. He describes in his oral history interview that he was also in charge of civil defense, where he trained staff members in crisis management and first aid:

"Once, we had a fire at [Ewart Hall]. My people, my people whom I trained, put [out] the fire before the [firemen] came ... In '67, I helped all the Americans [evacuate during the war] ... I took them to Alexandria, put them on a bus to a hotel, and spent the night. And brought them from Alexandria, to Malta or Cyprus or some place. And I was the only Egyptian with them."

Rashidi's example of selfless service reflects the broader legacy of the Division of Extension and its successor programs, which, from their inception, aimed to bridge gaps -- whether through education, cultural exchange or social services. From addressing public health issues to creating new opportunities, SCE's enduring legacy of connection and care continues today.

As Rashidi put it, "CACE is [the] backbone of education in Egypt. ... Anywhere you go, you find our graduates, CACE graduates, holding very good jobs. ... Whether they are police officers, drivers, ministers, under secretaries of state -- they are everywhere, like nerves in a body."