By Em Mills and Devon Murray

Do you ever ask yourself, "Why do I keep attracting the same kind of partner?" or "Why do I find myself in the same types of relationships -- which always seem to end -- over and over again?"

Getting to know your attachment style may answer some of these questions and help you break free from a seemingly endless cycle. Attachment theory explores the relationship, or emotional bond, between a child and their primary caregiver. Such a bond plays an integral part in developing a child's sense of security, which later affects their adult relationships, according to Nour Zaki, visiting assistant professor in AUC's Department of Psychology.

The theory includes four attachment styles that are defined by our perceptions of ourselves and others: secure, anxious, avoidant and disorganized. "Knowing your style can help you understand your needs in relationships, and how to express them in a healthy way," says Zaki, whose research focuses on attachment theory.

'Cradle to Grave'

The theory was initially developed by researchers John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth in the mid-to-late 20th century. Before their work, the general consensus was that human and animal babies stayed close to their mothers because they associated them with nutrition.

"Bowlby started to think, 'There is something emotional here. It's not just about food; it's about seeking proximity,'" says Zaki. "Babies cannot survive on their own. They need to be close to an adult figure who is able to provide that sense of safety."

This adult is known as the "primary caregiver" in attachment theory. "Typically, this is a child's mother but not always," Zaki explains. "It can be the father, an adoptive mom, a grandparent or even an older sibling in some cultures."

At around six to nine months, a baby begins to differentiate between caregivers and strangers. "At this stage, we begin to see stranger anxiety and separation anxiety, displayed by a clear preference for certain caregivers. These are healthy signs of attachment," Zaki says.

Depending on the quality and consistency of care a child receives from their primary caregiver, their attachment will likely develop in line with one of the theory's four styles: "If a caregiver is attuned to their child's needs, the child learns that they are worthy of attention and that they can rely on others," Zaki says. "This usually leads to secure attachment -- the belief that we deserve love and can trust other people."

Bowlby has a famous saying: "Attachment stays with you from the cradle to the grave." Your relationship with your caregiver is a major player in developing your core beliefs, or "internal working models," which dictate how you see yourself and others, how comfortable you are setting boundaries as well as other aspects of relating to people.

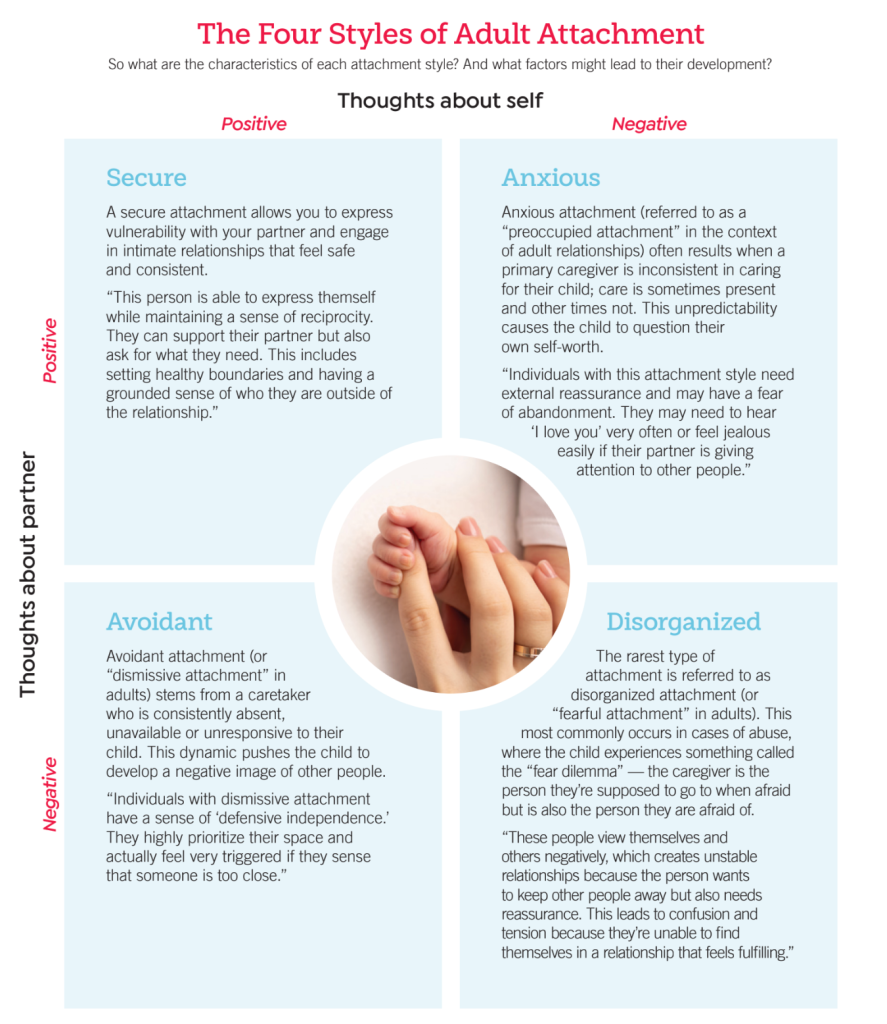

The Four Styles of Adult Attachment

So, what are the characteristics of each attachment style? And what factors might lead to their development?

Secure

A secure attachment allows you to express vulnerability with your partner and engage in intimate relationships that feel safe and consistent.

"This person is able to express themself while maintaining a sense of reciprocity. They can support their partner but also ask for what they need. This includes setting healthy boundaries and having a grounded sense of who they are outside of the relationship."

Anxious

Anxious attachment (referred to as a "preoccupied attachment" in the context of adult relationships) often results when a primary caregiver is inconsistent in caring for their child; care is sometimes present and other times not. This unpredictability causes the child to question their own self-worth.

"Individuals with this attachment style need external reassurance and may have a fear of abandonment. They may need to hear 'I love you' very often or feel jealous easily if their partner is giving attention to other people."

Avoidant

Avoidant attachment (or "dismissive attachment" in adults) stems from a caretaker who is consistently absent, unavailable or unresponsive to their child. This dynamic pushes the child to develop a negative image of other people.

"Individuals with dismissive attachment have a sense of 'defensive independence.' They highly prioritize their space -- and actually feel very triggered -- if they feel that someone is too close."

Disorganized

The rarest type of attachment is referred to as disorganized attachment (or "fearful attachment" in adults). This most commonly occurs in cases of abuse, where the child experiences something called the "fear dilemma" -- the caregiver is the person they're supposed to go to when afraid, but is also the person they are afraid of.

Are We Doomed?

You may be wondering, "Will I always push people away then?" or "Am I stuck in this pattern forever?"

"No one's attachment style is fixed," Zaki affirms. While you may have a tendency to fall into a certain pattern, it can be different in each individual relationship depending on your dynamic with your partner.

"Understanding where your patterns come from can give you a sense of empowerment instead of feeling like you're on autopilot, because what we're used to in terms of relationship dynamics eventually becomes like autopilot, right?" says Zaki.

She is also quick to note that each attachment style has strengths and weaknesses. "It's not just about understanding our vulnerabilities, but also our strengths, because each attachment style has its own points of strength." For example, the independence that comes with avoidant behavior can be beneficial in the workplace, where one might be more inclined to push themselves and take the initiative before being asked to do something. It all depends on the ability to express your needs in a clear, healthy way.

"If you feel like you've had a challenging childhood experience or are facing relationship dynamics that aren't ideal or healthy, looking at these dynamics can help put you on the road to self-understanding from a developmental perspective." says Zaki.

Breaking the Cycle

Zaki's interest in attachment theory developed as she worked on her PhD dissertation at Universidad Catolica San Antonio de Murcia in Spain, where she explored the transition to motherhood and how a mother's attachment style relates to how she views herself as a future mom. She is interested in how attachment styles are passed across generations, and how such cycles are broken.

"We often hear people say that despite wanting to raise their children differently than their parents, they end up doing or echoing the very things they heard growing up," she says. "Identifying and understanding one's attachment style empowers us to work on our vulnerabilities and insecurities early on, so we can avoid becoming triggered while transitioning to parenthood. This developmental approach to parenting is very powerful."

Hoping to support the next generation, Zaki conducts workshops and lectures in Egypt and collaborates with a number of international organizations, including the Association for Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health. She also teaches and conducts research related to developmental psychology and mother-infant attachment in her Attachment Lab at AUC, which recently received a research support grant from the University for her latest research project on the intergenerational transmission of attachment between mothers and their babies.

Her advice for readers? "It's never too late."