A visual arts professor delves into AI’s digital brush — capable of copying form but never feeling the heart behind the art.

Could a robot have painted the Mona Lisa? Will AI ever be the next Van Gogh? Brenda Segone is asking these very questions as she analyzes what it means for a machine learning model to “create” art.

Assistant professor of design history and theory in the Department of the Arts, Segone has long been fascinated by artificial intelligence and its potential applications. In her research, she investigates AI’s text-to-image capabilities, analyzing how AI takes textual inputs and transforms them into visual outputs.

What makes ChatGPT different from Caravaggio?

Everything, Segone argues.

“Developers like to make it seem like AI is human. More than human even, superhuman, synthetic human,” Segone explained. “But this isn’t true. AI is a powerful tool, but it does not function like a human. It lacks the key human traits of subjectivity and perspective.”

For an artist, subjectivity, or one’s unique viewpoint, is what allows a work to move beyond visual appeal and speak to the viewer. AI lacks this unique viewpoint and, therefore, lacks a connection to the audience.

“Developers like to make it seem like AI is human. More than human even, superhuman, synthetic human. But this isn’t true. AI is a powerful tool, but it does not function like a human.”

In her research, Segone compared two images, one created by Lara Baladi, associate professor of practice in the Department of the Arts, and the other by an AI image generator. Blending the disciplines of computer science, neuroscience and design, Segone evaluated how that differs from a human artist. Perspective and purpose emerged as the key differences.

To illustrate the limits of AI creativity, Segone highlighted the mistakes made in generating images. AI text-to-image is based on data sets, in which AI models predict visual patterns that emerge from those data sets. When AI warps reality, it is not doing so with artistic intent, but instead, it is an error in data prediction.

“I thought AI would have more playfulness, more imagination,” Segone explained. “But in its current form, it’s just regurgitating images it has been fed without reason.”

Segone analyzed Marc Chagall’s Self-Portrait with Seven Fingers. Extra or distorted fingers are a common error in AI-generated images, but the extra fingers in Chagall’s painting are an intentional choice, meant to indicate the specific vision of the artist. The viewer can interpret the meaning behind it even if the choice does not follow the concrete rules of visual reality. “This is what makes it art — the ability to make those choices,” Segone argued.

Emphasizing the value of human-made art, Segone explained how there is a different law of physics in artwork. “Artists and designers capture the mystery of perception by creating worlds that don’t obey the laws of physics, and yet they still make sense,” she expressed. “This can’t be replicated by AI because AI systems don’t understand the laws of perception.”

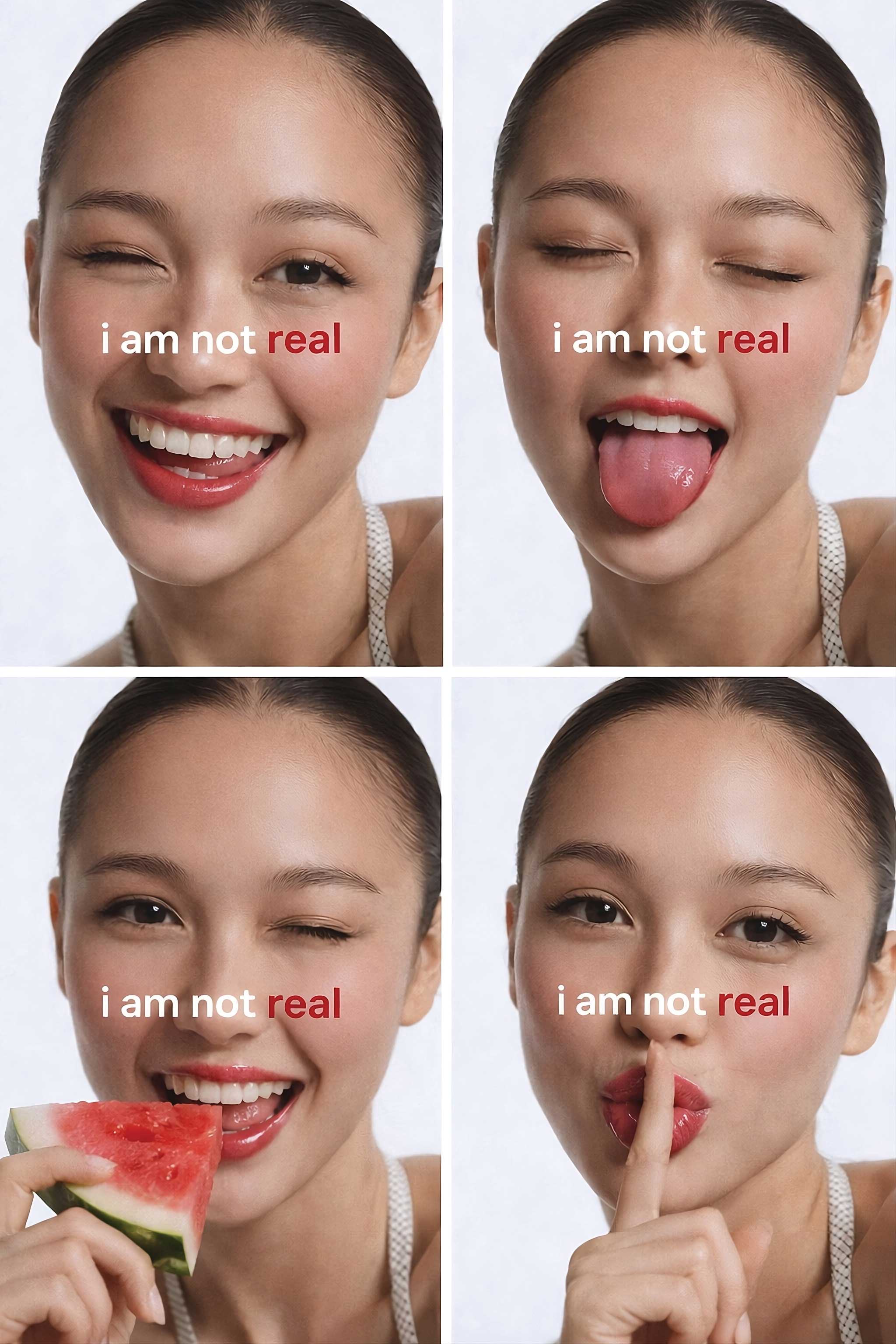

A skin care campaign by student Maya El Agizy using an AI-generated model

Currently, Segone teaches a course at AUC on this very topic: Art and Design Making from the Digital Era to AI. Like her research, she uses the class to build AI literacy among the next generation, teaching AI’s capabilities and its limitations. “Students and designers alike need AI literacy. Many students aren’t aware that AI is based on prediction, and if they don’t know that, they can get fooled and overly fear the tools,” she said.

There are still ways for designers to use and improve AI. “The field is developing rapidly. Nobody will ever understand all parts of the model, but we need to be constantly learning,” she stated. “As an art historian, working in a field as it is unfolding in the present is fascinating.”

Another risk of AI is its implicit biases, depending on where the data sets used to train these models came from. Segone believes practitioners based in the Middle East have a duty to continue improving these models. “It’s our responsibility to guarantee rich data sets from this region so that there are fewer biases in the models,” she said. “We must ensure AI tools are equitable.”

“Many students aren’t aware that AI is based on prediction, and if they don’t know that, they can get fooled and overly fear the tools.”

For now, Segone warns designers not to over-rely on AI tools. The human side of art will be valued increasingly as AI work becomes more common. “We might even see stickers on artwork showing that it’s ‘AI-free,’” she said.

In its current state, it doesn’t seem like AI will be creating any artistic masterpieces in the near future. That power still remains with humans and with the stories molded by our unique perspectives. Segone hopes artists will continue developing their own artistic voices and use AI not as a crutch but as a palette. “Keep exploring your own mistakes and making your own reality,” she affirmed.

“Developers like to make it seem like AI is human. More than human even, superhuman, synthetic human. But this isn’t true. AI is a powerful tool, but it does not function like a human.”