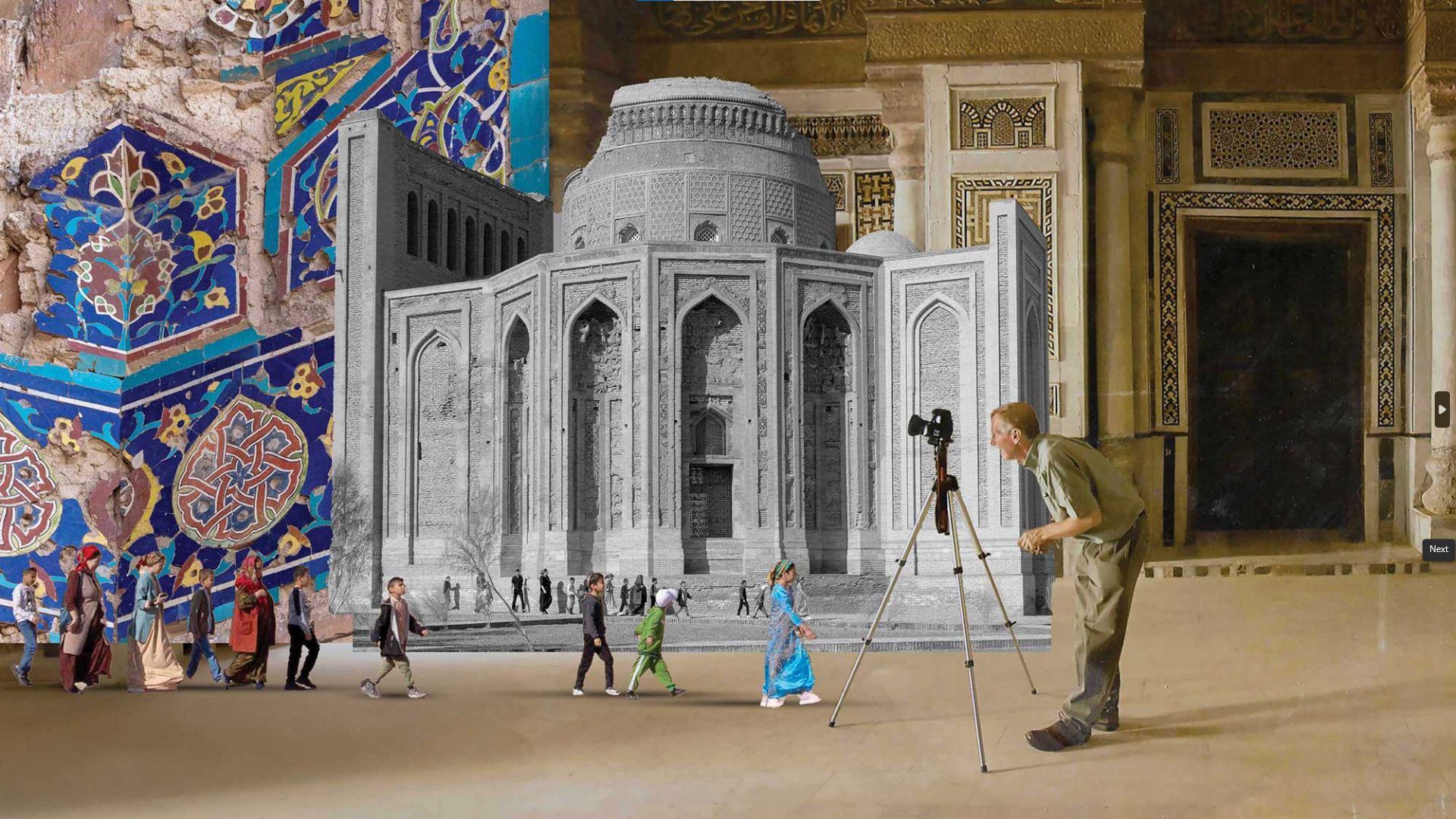

From Istanbul to Central Asia, one scholar’s lifelong pursuit of color, craft and architectural memory traces Islamic tilework’s preservation of history.

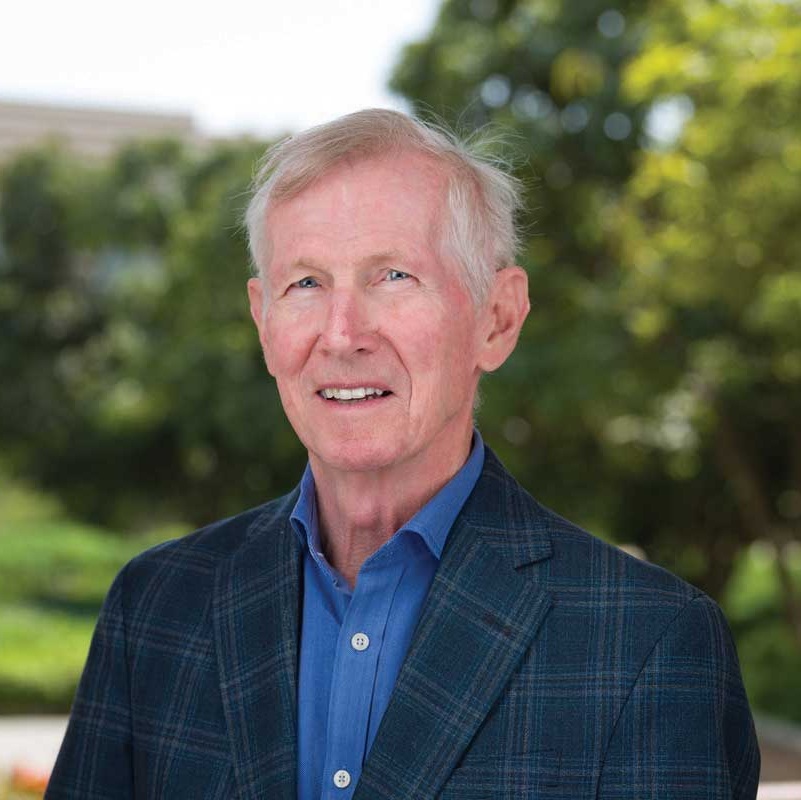

The summer after his first year of university, Bernard O’Kane boarded a train from Ireland to Istanbul, emerging in a world of brightly colored tiles. The next year, he took the same train to Istanbul and boarded a boat to Alexandria to see the architecture of Egypt. He continued this habit a third summer, venturing further east from Turkey into Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon. The colorful art and architecture of the Islamic world captured O’Kane in a way he wasn’t able to shake then.

Now a professor of Islamic art and architecture in the Sheikh Hassan Abbas Sharbatly Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations, O’Kane’s love of travel never faded. He regularly visits places in the Middle East and Central Asia to investigate the historical architecture and tilework around the region.

Most recently, O’Kane traveled to Turkmenistan, researching the tilework of monuments in Kuhna Urgench. This historical site was the capital of the Khorezm region with monuments including a mosque, the gates of a caravanserai, fortresses, mausoleums and a 60-meter-high minaret. O’Kane was drawn to the tilework, whose soulful colors have endured more than seven centuries.

“Tilework is a particularly important form of Islamic art. It serves as a colorful, vibrant way to shape the identity of sacred and secular spaces,” he said.

“Tilework is a particularly important form of Islamic art. It serves as a colorful, vibrant way to shape the identity of sacred and secular spaces.”

For O’Kane, photography goes hand in hand with his love of tilework, capturing the striking colors. “It is how I became interested in art history in general,” he explained. “I was an amateur photographer doing my own developing and printing when I was 10 years old. It’s a very important tool for this field.”

O’Kane had his eye on studying the monuments of Kuhna Urgench for many years, but despite a clandestine foray from Uzbekistan before the fall of the Soviet Union and one shortly after, these trips allowed only basic study. He realized he’d need an extremely detailed telephoto lens to capture the intricacies. In 2024, professional camera in hand, O’Kane returned to Kuhna Urgench and was able to analyze the tile.

“I discovered that on the Mausoleum of Turabk Khanum, there were combinations of tile types that no one had previously recognized, combining tile mosaic with overglaze-painted tiles,” O’Kane explained.

The tilework of Kuhna Urgench is significant both to Central Asia and the world of Islamic art due to its uniqueness and preservation. The longevity of tiles makes them a keystone of heritage preservation, especially in Islamic art and architecture, which focuses on the display of ornate geometric patterns and designs.

Another of Kuhna Urgench’s monuments, the tomb of the renowned Sufi saint Najm al-Din Kubra, involves underglaze painted tiles incorporating alphanumeric placement marks, with the Persian alphabet and numbers written on the tiles in different combinations. “It’s unique to the region,” O’Kane stated.

The distinctness of the setting, paired with the visual cohesion of the monuments, has made it worth the professor’s nearly three-decade-long wait. “The monuments that survive in Kuhna Urgench are some of the most striking examples of these kinds of tilework,” he shared.

“There is a density of tilework and a quality that you rarely see in the Islamic world. ”

The colors of the tiles are what intrigue O’Kane, as well as their ability to last from the 14th century until today. “Color is an extremely important factor in my research,” he said. Pointing to the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo as an example, O’Kane explained that its carved stucco decoration was almost certainly highly colored when it was first built.

Tilework, like that at Kuhna Urgench, is much more permanent than the paint applied to stucco, woodwork or stone. “It keeps its color beautifully over centuries,” he said.

O’Kane has spent four decades traveling and taking photographs of Islamic tilework. “Working at AUC has been a wonderful opportunity to immerse myself in the monuments of Cairo, one of the most architecturally rich cities in the world,” he said.

As he broaches retirement, O’Kane plans on combining the body of his work into one major project. “I would like to write a comprehensive book on tilework in Islamic architecture, using my own photographs,” he stated. “I’ve been introduced in lectures around the world as being the person who has more photographs of Islamic architecture than anybody else in the world, which I hope to continue to live up to.”