While AUC's New Cairo campus is surrounded by modern developments, Cairo as a whole is a treasure trove of historic Islamic monuments. We spoke to two of AUC's experts on Islamic architecture about some of their favorite buildings and the fascinating history around them, including a few hidden gems -- some only recently reopened to the public.

What makes Cairo unique is its exceptionally long history of urban development as a capital city, combined with its lack of devastating conquests such as those suffered by Baghdad or Damascus. "Of any Islamic city, Cairo probably has the greatest range and density of monuments," remarks Bernard O'Kane, professor of Islamic art and architecture. "It has wonderful monuments from all the major dynasties -- Fatimid, Ayyubid, Mamluk, Ottoman and Khedival.

Now open after 10 years of renovations is the Suleiman Pasha Mosque inside the Citadel of Saladin. The mosque is one of the earliest Ottoman monuments in Cairo, built soon after the conquest of Egypt by the Ottomans in 1517. For that reason, Pascale Ghazaleh '93, '97, associate professor and chair of AUC's Department of History, describes the mosque as "a perfect balance between Mamluk and Ottoman styles," emphasizing its unique position between two of Egypt's historical dynasties. "It has quite a warm and intimate feeling," observes Ghazaleh, in contrast with the imposing scale of the surrounding Citadel walls.

The Suleiman Pasha Mosque also has "one of the finest painted interiors of any 16th-century Ottoman building" anywhere in the world, says O'Kane, who affirms that original Ottoman artwork of this type can hardly even be found in Turkey, as most mosque interiors were painted over in the 19th century. For art historians, the mosque is "a fabulous example of the early Ottoman style," as O'Kane puts it.

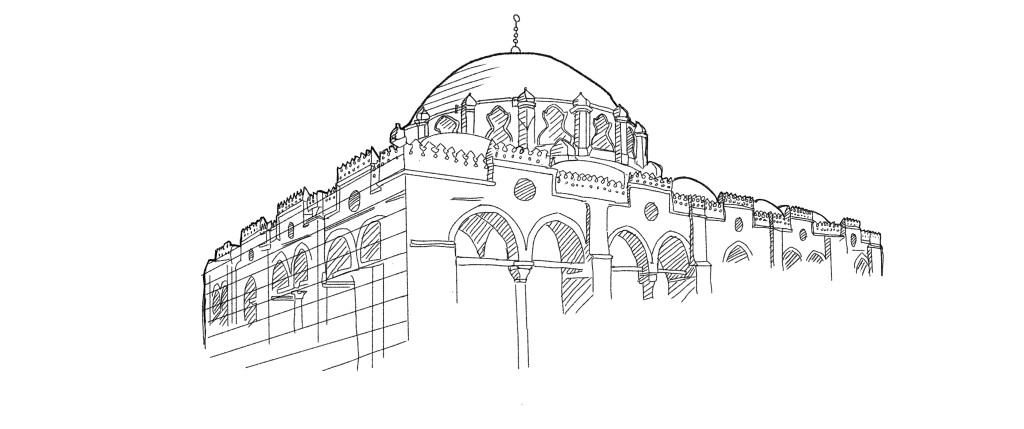

Another standout monument of Cairo is perhaps more well known: the massive Sultan Hasan mosque-mausoleum complex. "The fact that it's so big is surprising, given that it was built while the Black Death was raging in Egypt -- which you would automatically think would be an adverse factor, as there wasn't a lot of labor or money to go around," says O'Kane. "In fact, the opposite was true: Because so many complete families died, there was no one left to inherit, and the money went into the state coffers instead."

Visitors may also notice that the walls of the complex are pockmarked, particularly those facing the Citadel. These were not part of the original design, to put it mildly, O'Kane explains. "When a Mamluk sultan died, there was no fixed method of succession," says O'Kane. "So frequently, coteries of emirs battled each other for power in the streets.

At one stage, they found that the walls of the Sultan Hasan complex were so massive that they could support cannons, which these groups dragged up onto the roof and started firing toward the Citadel. Not surprisingly, the Citadel fired back. Fortunately, the walls were so massive that they just left a few dents in the stonework without causing the building to collapse." The fortress capabilities of the complex proved such a threat to the Citadel's supremacy that Sultan Al-Mu'ayyad had its staircases demolished to prevent cannons from being brought onto the roof, says O'Kane.

"Of any Islamic city, Cairo probably has the greatest range and density of monuments."

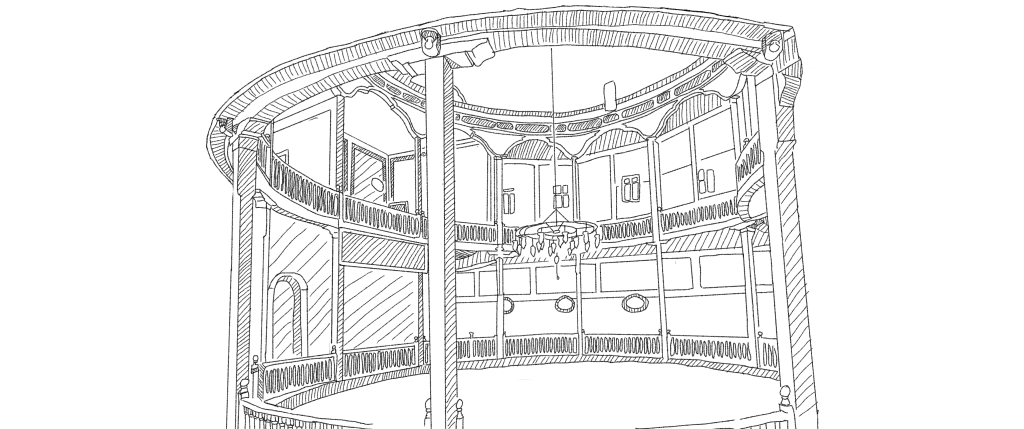

Just down the street from Sultan Hasan is one of Ghazaleh's favorite architectural sites, reopened after years of painstaking restoration. The Sama'khana is a historic Sufi theater built by the Mevlevi Order for mystical performances of song and dance.

According to Ghazaleh, the building is "a palimpsest of different styles" and sports a brilliant 19th-century, Ottoman-style painted wooden ceiling and dome, which have been restored by a joint Italian-Egyptian team of artisans. "They did everything very carefully by hand, which is in stark contrast to many other restoration projects that we see being undertaken by contractors," she notes. After years of work, the Sama'khana is open once again and hosts live performances open to the public.

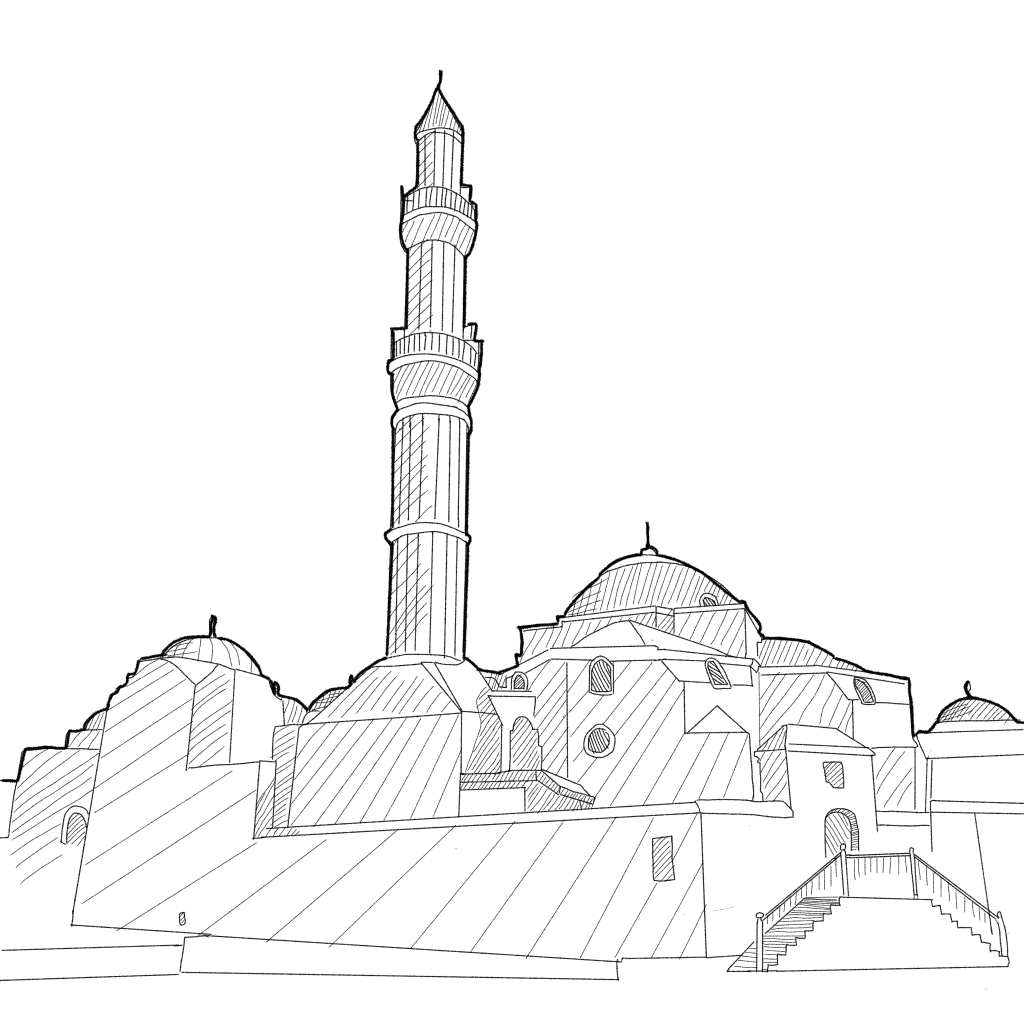

Ghazaleh concludes with a site far from the typical medieval core of Islamic Cairo. The Sinan Pasha Mosque in Boulaq is "off the beaten path in the sense that it's in a part of Cairo that was far from the center of religious and cultural life," better known as a fluvial trading hub. The mosque "gives an idea of how diverse Ottoman rule was and how it adapted to different environments," she explains. Seeing the Sinan Pasha Mosque in the middle of modern Boulaq, a dense neighborhood of high-rise office towers and apartments, is like seeing an old friend," says Ghazaleh. "It feels somehow comforting."