AUC is preserving and digitizing a rare collection of newly acquired Arabic and Islamic manuscripts.

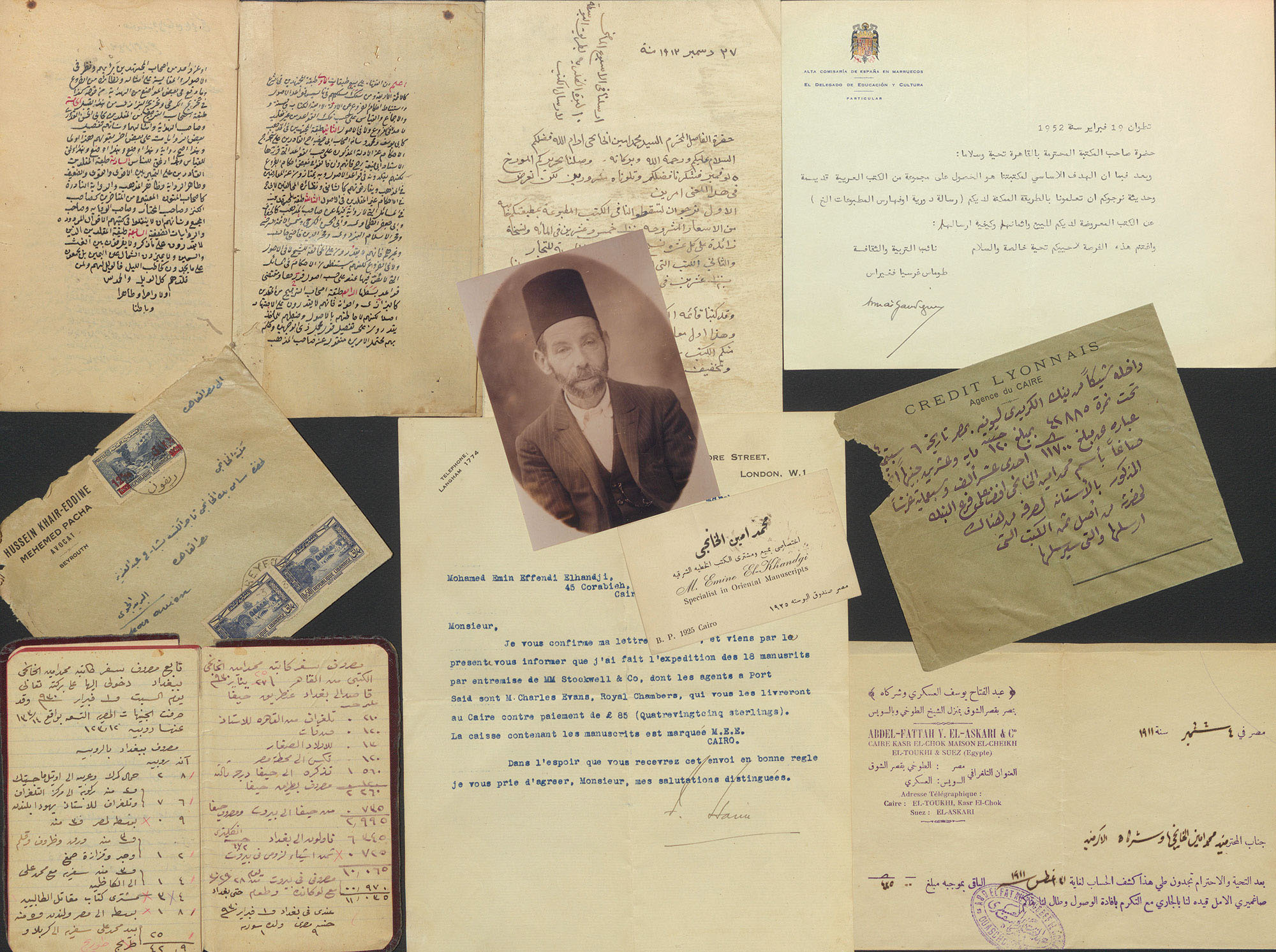

From the 1920s to the 1960s, Khanji Publishing House played a leading role in editing, printing and distributing important Arabic and Islamic manuscripts. Last fall, in collaboration with five U.S. institutions — the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton University, New York University, the University of Michigan and the College of Charleston — AUC acquired the Maktabat al-Khanji Archive — a rare collection of thousands of documents covering the day-to-day business of the publishing house.

“The archive tells a story of where passion, business and culture intertwine."

Within the archive lie secrets, relationships and manuscripts that reveal new information about the history of the Arab-Islamic literature and publishing world. Now responsible for preserving this collection, AUC’s Rare Books and Special Collections Library (RBSCL) will be the first to hear and share these tidbits of the region’s history with the world.

What’s in an Archive?

With approximately 5,600 items, the collection provides a peek into the Arabic and Islamic publishing scene of the early 1900s, when Mohamed Amin al-Khanji (1865-1936) settled in Cairo to pursue his passion for searching, identifying and selling manuscripts. After starting his business, al-Khanji and his family quickly filled a pivotal role in the translocation of tens of thousands of Arabic manuscripts — when such trade was legal — including some of the most important collections worldwide.

“Al-Khanji’s interest in books and manuscripts started during his childhood in Syria, when he realized that local inhabitants don’t pay attention to the value of a manuscript,” says Amr Omar, assistant director at RBSCL and project supervisor. “He began his business in Istanbul, but due to tight restrictions on publishing, he had to move to Cairo, where it’s unfettered.”

The Maktabat al-Khanji Archive not only contains the history of new or previously lost manuscripts, but also correspondences, invoices, book orders, price lists and personal documents that reveal the everyday life of the business and its affiliates. “The archive tells a story of where passion, business and culture intertwine,” says Omar.

"It often takes us several months to solve the enigmatic part of the collections — some of which date back more than 100 years."

After receiving the archive, a team of library specialists was formed to begin an instant conservation treatment, a process that Omar says was “much needed” before each item in the collection could be scanned. Less than a year after the acquisition, the team has accomplished both tasks.

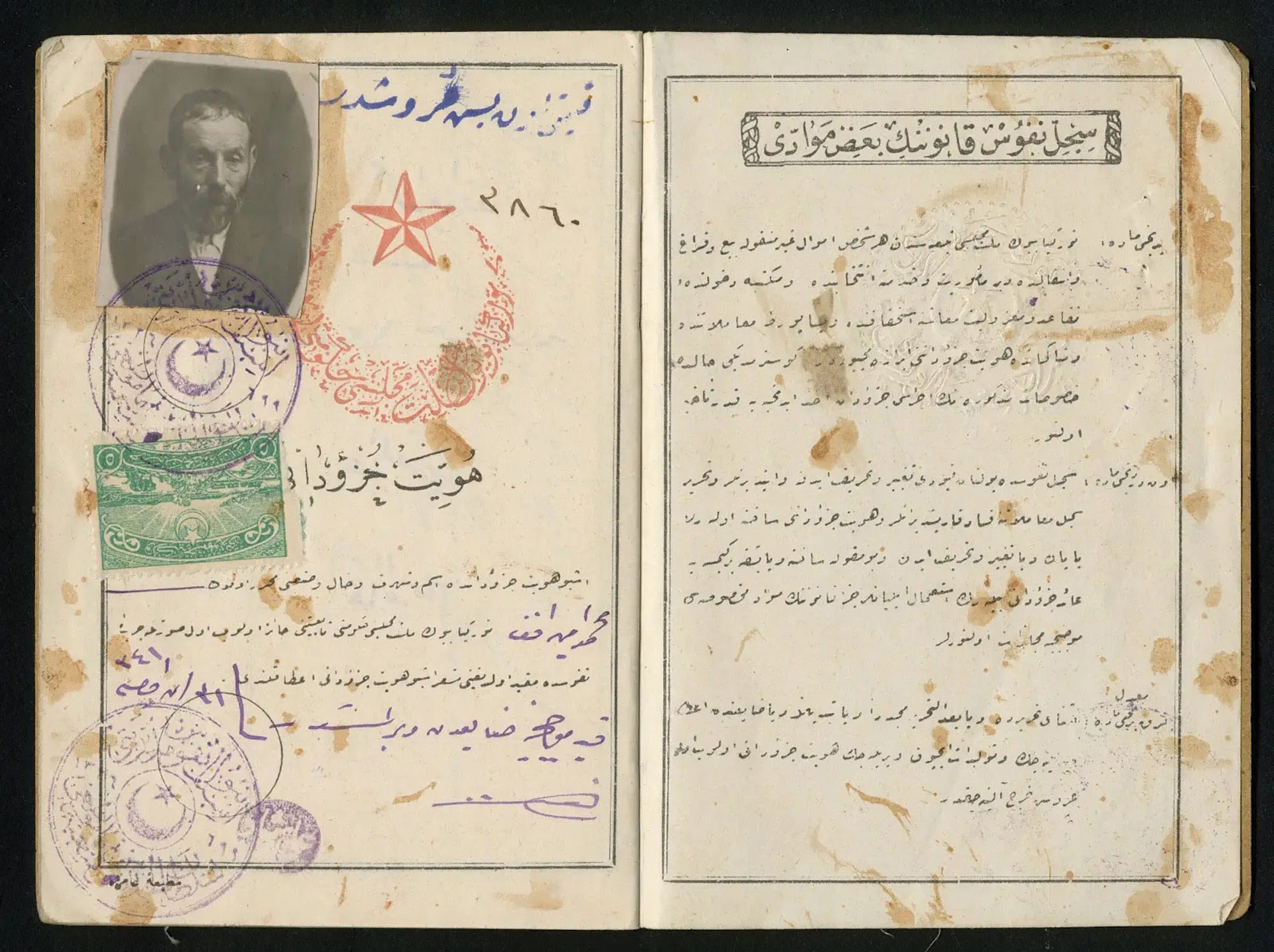

Mohamed al-Khanji’s residence permit

Mohamed Amin al-Khanji

“Processing archival material is not as easy as it sounds,” says Omar. “It often takes us several months to solve the enigmatic part of the collections — some of which date back more than 100 years — since we need to analyze all scattered bits and pieces. Once we understand the ‘skeleton’ or primary content, we dive into a detailed classification process before placing each item under the right category.”

The archive is also helping form a more complete history. One way is by locating lost manuscripts. “We often only have a name, title or manuscript description and price,” says Omar. “We can sometimes find these in manuscript lists published by a collection, library or museum, but we often require further information to trace the manuscript back to its origin,” says Omar. “It’s a challenging puzzle.”

"We can sometimes find these in manuscript lists published by a collection, library or museum, but we often require further information to trace the manuscript back to its origin. It’s a challenging puzzle.”

Rediscovering Lost Histories

Omar explains that the items in the archive will provide a new lens to historians, especially since most accounts on the Middle East come from Western or external sources. Unlike those, the Maktabat al-Khanji Archive exposes interactions, relationships and accounts from within the Arab world, revealing internal dynamics.

“The piece that attracted me the most, even though the collection has not yet revealed all its secrets, is the set of materials related to Ta’rikh Baghdad Madinat al-Salam (History of Baghdad, City of Peace),” says Omar. “This piece is a monumental biographical encyclopedia written by Khatib Al-Boghdadi, featuring more than 7,800 theologians, poets, jurists and intellectuals who either lived in or passed through Baghdad.”

“This piece is a monumental biographical encyclopedia written by Khatib Al-Boghdadi, featuring more than 7,800 theologians, poets, jurists and intellectuals who either lived in or passed through Baghdad.”

Omar explains that the original manuscripts of this book were considered “lost” by many scholars until al-Khanji was successfully able to identify a number of them in libraries, museums and private collections across Iraq, Turkey and Egypt. He presented the first-ever Arabic edition in the early 1930s in partnership with an Iraqi publisher, Noaman Al-Azami.

“Publishing such an encyclopedia at that time was a severe risk, as the world was facing the Great Depression and al-Khanji himself was not fully recovered from a financial crisis,” says Omar. “However, the book was banned shortly after the 13th volume saw the light of day due to the perception that Imam Abu Hanifa’s significant contributions to fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) weren’t sufficiently recognized.”

After long discussions and negotiations with Al-Azhar, al-Khanji was able to resume the publishing process, supplementing the book with complementary volumes, possibly as one of the conditions for approval. “Surprisingly, after all his tremendous efforts and suffering, he — for an inexplicable reason — never reprinted that book again,” says Omar.

The debacle reveals the dedication and delicate balancing act required of al-Khanji to continue disseminating information through his books and manuscripts. Now, his work and legacy will emerge once more, thanks to the AUC archive and its digital lab.