Discover how ancient Egypt’s simple, local diet still shapes staples on Egyptian tables today with professor Mennat-Allah El Dorry's guide to ancient Egyptian cuisine.

Have you ever wondered what the ancient Egyptians would have eaten in the absence of homemade molokhiya and street shawarma? Mennat-Allah El Dorry ’05, assistant professor and chair of Coptic studies in the Department of Sociology, Egyptology and Anthropology, studies Egyptian food history.

Here’s what she told us about ancient Egyptian eating habits, and how we know.

What was ancient Egyptian cuisine like?

When it comes to ancient Egyptian cuisine, we’re limited to the evidence we have. We know a lot about the raw ingredients, but we don’t know how they were put together. We can assume the cuisine as a whole was a very simple, rural one, but it’s difficult to describe in detail. Yet we know that it was largely based on land and available resources, with a bit of import and trade of products with others. For example, pomegranate was introduced in the New Kingdom from the East. It was a very local, seasonal diet, and this only changed in the last 100 years, as is the case with many traditional cuisines.

In what ways do we see remnants of the ancient Egyptian cuisine in Egyptian food today?

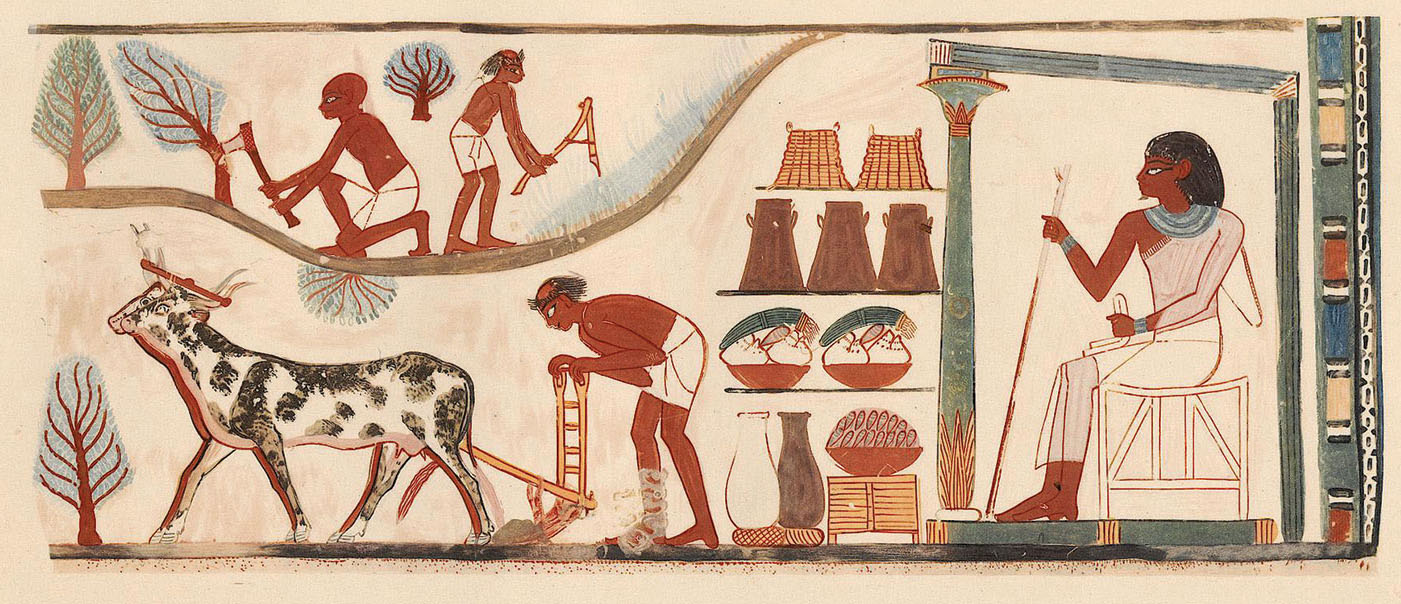

There are specific products that are continuously used throughout Egyptian history. Khass baladi, or local lettuce, is seen in ancient Egyptian tomb scenes and continues to be used until now; it’s a staple of every baladi table. So are spring onions and attah, an ancient cucumber variety that can also be found today. Bread was an absolute cornerstone of the ancient Egyptian diet and is still in the modern Egyptian diet. These are staples of the ancient diet that have remained. There are also products that we assume existed but don’t have hardcore evidence for, like fermented cheese, while there are products that we have plenty of evidence for, such as dairy products, beef, duck, geese, fish, pork and other meats.

Khass baladi, or local lettuce, is seen in ancient Egyptian tomb scenes and continues to be used until now; it’s a staple of every baladi table.

An agricultural scene from the tomb of Nakht in Thebes, showing food, including spring onions — New Kingdom

How do we know about ancient Egyptian cuisine?

Through several types of archaeological evidence:

Animal remains or bones reveal slaughter marks, which tell us which cuts of meat people wanted at the time. Some remains show evidence of burning. For instance, the jaw of a pig will have parts that are singed if it’s been spitroasted. Plants reveal how and where people were sourcing their products and what they were eating. Whether animal or plant remains, we find the wastes or leftovers — bones, peels, seeds — and not what people were actually eating.

Tombs are a tool unique to ancient Egypt. Since ancient Egyptians believed in an afterlife, they prepared their tombs to enable them to continue living. They had beautiful tomb scenes that were meant to symbolically come alive in the afterlife, and some included big offering tables. Food offerings were also made to the dead, which could include fancy cuts of meat, fish, geese, ducks, plants, fruits and grains — leaving behind physical remains.

Human remains are special because bones, enamel and calculus on teeth allow for chemical analysis that helps us determine specific food groups that were eaten. Ancient Egyptians mummified the dead, so they removed the stomach and entrails, but when the tradition of mummification ended, we started getting remains of the last meals in the stomach. We also have tons of text from different time periods, like letters, contracts and delivery receipts, which tell us how people managed food, agriculture and animal products.

Pottery containers used to prepare and store food are also revealing. Based on their shapes, we can extrapolate what they were used for. We can additionally take DNA samples from the wall of a pot to find out its contents (if it held a plant or animal and which kind of animal). We can also determine the fat percentage of the food and then hypothesize what was being prepared in this dish or pot.

Ovens from different time periods also inform us about what people were cooking based on their shapes. Physical tools like grinding stones, knives and ladles throughout history enable chemical analysis, revealing how these tools were used. For instance, we can figure out the amount of starch on a blade, and through that, figure out what it was regularly or last used for.

Ancient Egyptians mummified the dead, so they removed the stomach and entrails, but when the tradition of mummification ended, we started getting remains of the last meals in the stomach. We also have tons of text from different time periods, like letters, contracts and delivery receipts, which tell us how people managed food, agriculture and animal products.

Were there upper- and lower-class distinctions in ancient Egyptian cuisines?

The elites or rulers would have had access to more animal-based protein, especially beef, and they would have eaten that more regularly. They would have had access to products like honey, which was a luxury at the time. Elites would have been drinking more wine, a high-end commodity, while the masses would have had more regular beer consumption. There was a variety of different types of wine, probably grape wine, date wine and maybe pomegranate wine. Beer in ancient Egypt would have been very thick, nutritious, low in alcohol content but rich in minerals. And whether beer or wine, people may have had to drink them using a strainer because they would have had a lot more impurities. The less wealthy would have eaten fish, pork and vegetables as well as bread and beer alongside these staples.

Honey and Date Nut Cake

1550 BCE

Source:

Ebers Papyrus, Leipzig University

The Ebers Papyrus is a medical text from ancient Egypt containing concoctions and recipes to address various ailments and diseases. This ‘cake’ is meant as a cure for coughs.

Ingredients:

1 cup dried dates, pounded to a powder

1/2 cup water

1 tsp honey

Method:

Mix date powder with water to make a loose paste.

Pour the mix into a well-heated pan, stirring continuously. When it boils, return to the bowl and mix with honey.

Divide the paste into small ball-shaped cakes and serve.

Tiger Nut Cake

18th Dynasty (1550–1295 BCE), New Kingdom

Source:

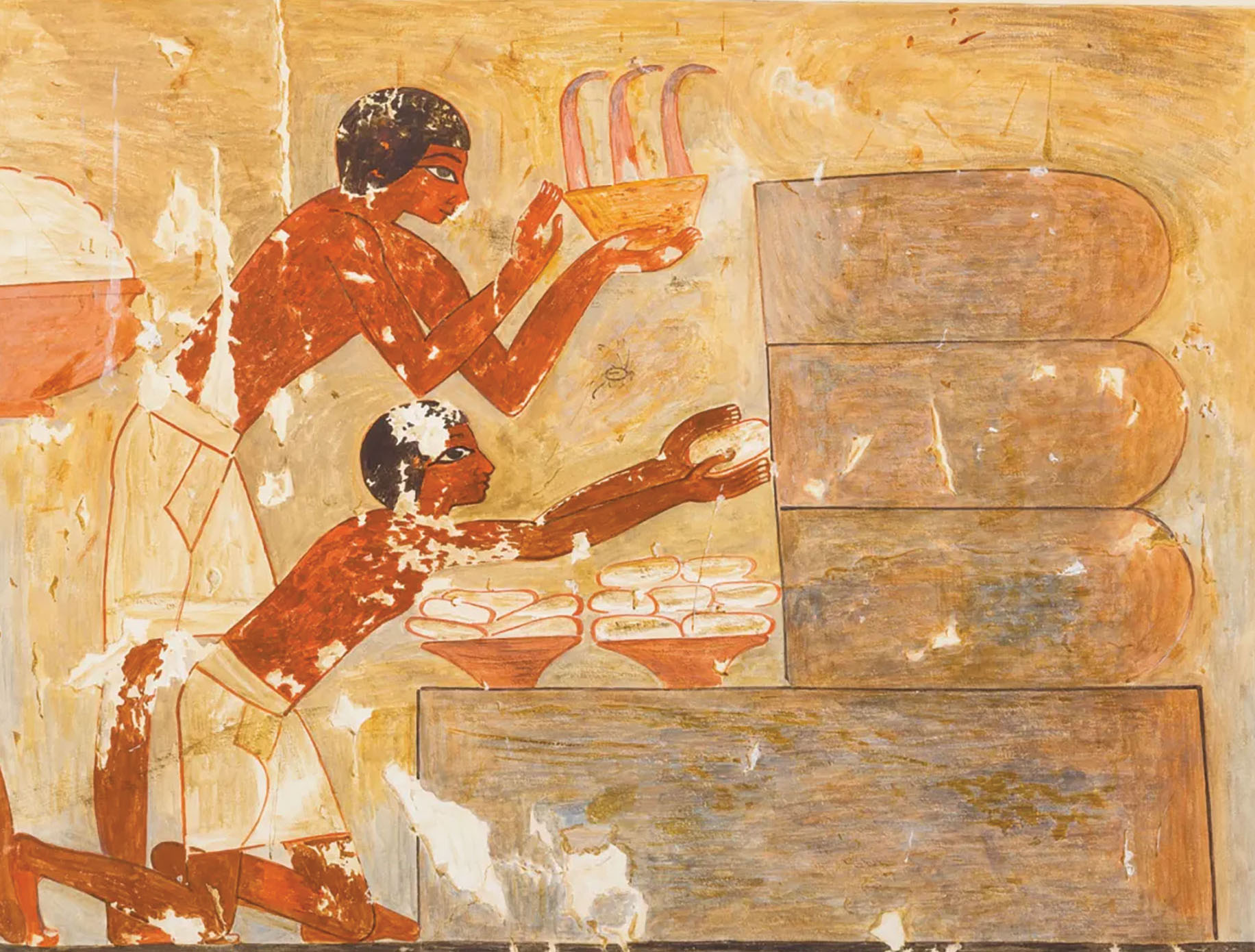

Wall from the tomb of Rekhmire, Thebes

A scene from the tomb shows men making a cake-like dish made of tiger nuts, giving us the closest thing to a recipe for food from ancient Egypt.

Ingredients:

1 cup tiger nuts ground into a powder

3/4 cup water

1/2 cup ground dates

2 tsp honey

Oil (for frying)

Method:

Mix the tiger nut powder with water and form a soft dough. Divide the dough into small ball shapes. Mix the ground dates with the honey into a purée.

To stuff each ball, create a small well with your thumb and fill the balls with the honey/date purée, close the gap and shape it into triangles.

Fry the triangles in oil, turning them frequently. Drain on a paper towel and serve cold.

Khass baladi, or local lettuce, is seen in ancient Egyptian tomb scenes and continues to be used until now; it’s a staple of every baladi table. So are spring onions and attah, an ancient cucumber variety that can also be found today.